In a quest to locate a book by Joseph Fischer and F.R.R.V. Wieser entitled The Oldest Map with the Name America of the Year 1507 and the Carta Marina of the year 1516 by M. Waldseemüller (Ilacomilus), I came across a poem by Lucia Perillo in the Beloit Poetry Journal and was probably the better off for it.

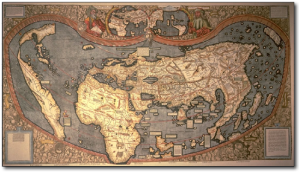

Here’s the map, followed by (fellow McGill-ian [McGill-er?]) Perillo‘s poem:

The Oldest Map with the Name America

1.

In Martin Waldseemuller’s woodblock, circa 1507,

the New World is not all there.

We are a coastline

without substance, a thin strip

like a movie set of a frontier town.

So the land is wrong and it is empty,

but for one small black bird facing west,

the whole continent outlined with a hard black edge

too strictly geometric, every convolution squared.

In the margin, in a beret, Amerigo Vespucci

pulls apart the sharp legs of his compass–

though it should be noted that instead of a circle

in the Oldest Map With the Name America

the world approximates that shape we call a heart.

2.

The known world once stretched from my house

to the scrim of trees at the street’s dead end,

back when streets dead-ended instead of cleaving

into labyrinths of other streets. I was not

one of those who’d go sailing blithely

past the neighborhood’s bright rim:

Saturdays I spent down in the basement

with my Thingmaker and Plastigoop. . .

Sunday was church, the rest was school,

this was a life, it was enough. Then one day

a weird kid from down the block pushed back

the sidewall of that edge, spooling me

like a fish on the line of his backward walking

fifty yards deep into the woodlot. Which

was barely wild, its trees bearing names

like sugar maple, its snakes being only

garter snakes. Soon the trail funneled

to a single log spanning some unremarkable

dry creek that the kid got on top of,

pointed at and said: You fall down there,

you fall forever. And his saying this

worked a peculiar magic over me: suddenly

the world lay flat and without measure.

So that when I looked down at the dead leaves

covering the ravine they might have

just as well been paint, as depth

became the living juice squeezed out

of space: how far

could you fall? Then the leaves shifted,

their missing third dimension reconfigured

into sound: a murmuring snap

like the breakage of tiny bones that sent me

running back to the world I knew.

3.

Unlike other cartographers of his day,

Waldseemuller wasn’t given to ornamenting his maps

with any of Pliny’s pseudohuman freaks

like the race of men having one big foot

that also functions as a parasol.

Most likely he felt such illustrations

would have demeaned the science of his art,

being unverifiable, like the rumored continents

Australia, Antarctica, which he judiciously leaves out.

Thus graced by its absence, the unknown world

floats beyond the reach of being named,

and the cannibals there

don’t have to find out yet they’re cannibals:

they can just think they’re having lunch.

4.

My point is, he could have been any of us:

with discount jeans and a haircut made

with clippers that his mother ordered

from an ad in a women’s magazine.

Nothing odd about him except for maybe

how tumultuously the engines that would run

his adult body started up, expressing

their juice in weals that blistered

his jaw’s skin as its new bristles

began telescoping out. Stunned

by the warped ukelele that yesterday had been

his predictable voice, the kid

one day on the short-cut home from practice

with the junior varsity wrestling squad

came upon a little girl in the woods,

knocked her down and then did something. . .

and then wrote something on her stomach.

Bic pen, blonde girl: the details ran

through us like fire, with a gap

like the eye of the flame where you could

stick your finger and not get burnt.

By sundown the whole family slipped–

and the kid’s yellow house hulked

empty and dark, with a real estate sign

canted foolishly in its front yard.

Then for weeks our parents went round

making the noise of baby cats

stuck up in trees: who knew? who knew?

We thought they were asking each other

what the kid wrote with the Bic–

what word, what map–and of course

once they learned the answer

they weren’t going to say.

5.

In 1516, Martin Waldseemuller

draws another map in which the King of Portugal

rides saddled on a terrifying fish.

Also, the name “America”

has been replaced by “Terra Cannibalor,”

with the black bird changed to a little scene

of human limbs strung up in trees

as if they had been put up there by shrikes.

Instead of a skinny strip, we’re now

a continent so large we have no back edge,

no westward coast–you could walk left

and wind up off the map. As the weird kid did,

though the world being round, I always half-expect

someday to intersect the final leg of his return.

6.

Here the story rides over its natural edge

with one last ornament to enter in the margin

of its telling. That is, the toolshed

that stood behind the yellow house,

an ordinary house that was cursed

forever by its being fled. On the shed

a padlock bulged like a diamond,

its combination gone with all the other

scrambled numbers in the weird kid’s head

so that finally a policeman had to come

and very theatrically kick the door in

after parking one of our town’s two squad cars

with its beacon spinning at the curb.

He took his time to allow us to gather

like witnesses at a pharoah’s tomb,

eager to reconstitute a life

from the relics of its leaving.

And when, on the third kick, the door flopped back

I remember for a moment being blinded

by dust that woofed from the jamb in one

translucent, golden puff. Then

when it settled, amidst the garden hose

and rusty tools we saw what all

he’d hidden there, his cache

of stolen library books. Derelict,

lying long unread in piles that sparked

a second generation of anger. . .

from the public brain that began to rant

about the public trust. While we

its children balled our fists

around the knot of our betrayal:

no book in the world had an adequate tongue

to name the name of what he did.

7.

Dying, Tamburlaine said: Give me a map

then let me see how much is left to conquer.

Most were commissioned by wealthy lords,

the study of maps being often prescribed

as a palliative for melancholy.

In the library of a castle of a prince

named Wolfegg, the two Waldseemuller maps

lay brittling for centuries–“lost”

the way I think of the weird kid as lost

somewhere in America’s back forty, where

he could be floating under many names.

One thing for sure, he would be old now.

And here I am charting him: no doubt

I have got him wrong but still he will be my conquest.

8.

Sometimes when I’m home we’ll go by the house

and I’ll say to my folks: come on,

after all these years it’s safe

just to say what really happened.

But my mother’s mouth will thin exactly

as it did back then, and my father

will tug on his earlobe and call the weird kid

one mysterious piece of work.

In the old days, naturally I assumed

they thought they were protecting me

by holding back some crucial

devastating piece. But I too am grown

and now if they knew what it was

they’d tell me, I should think.