This is the first draft of an article that I submitted two years ago for a special issue on “Monsters in the Margins” for the journal “Image/Text: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies:”

As it appears that the special issue is no longer happening (and I’m not entirely convinced that political cartoon research falls under the journal’s purview), I have decided to share my draft (and accompanying images) on this blog, mainly so I could send the link to my friend’s dad who’s a Civil War buff! Without further ado, I give you…

The Many-Headed Hydra: Monstrous Representations of Canadian Confederation and the American Civil War in Cartoons, 1861-1867

By: Amanda Murphyao

The period from 1861 to 1867 was a chaotic and formative one in both Canadian and American history. The American Civil War raged from 12 April 1861 to 9 May 1865, and the Dominion of Canada was officially established with the British North America Act on 1 July 1867 (Confederation). The symbol of the hydra in popular culture at the time represented the political crisis in both countries during the 1860s; in Canada, the hydra embodied the insurmountable terror of Canadian unification through Confederation, while in Union (Northern) states, the hydra symbolized the horror of Confederate (Southern) secession. Through the image of the hydra, unavoidable geo-political tensions were represented as a terrible mythical monster seeking to destroy the status quo of provincial autonomy (in the Canadian context) or federal unity (for the Union). This comparative analysis of cartoons, song lyrics, and editorials in the United States and Canada demonstrates how the myth of the hydra is rewritten during these crises, but ultimately leaves the multi-faceted challenges of federal politics unresolved. The notion of peaceful national unity in both countries remains a troublesome, many-headed issue in subsequent political cartoons.

Following a brief overview of early cartoons in the United States and Canada and a cursory introduction Canadian Confederation and the America Civil War, I will discuss the reptilian rhetoric associated with Confederate secession and Canadian Confederation. Focusing on two cartoons, “The Hercules of the Union, slaying the great dragon of secession” (1861) and « La Confederation!!! » (1864), I explain how the reality of secession and military conflict in the American cartoon is idealized while the looming threat of Confederation in the Canadian context is ultimately realized. During the early part of the Civil War, some predicted a quick Northern victory, while the lengthy and troublesome struggle of Confederation was predicted in the early 1860s by commentators in Canada. In both cases, they hydra was a useful trope to represent a repugnant, incomprehensible situation that seemed untenable. For pro-Union song writers and cartoonists, secession was a monster that needed to be slain for the restoration and reunification of the United States. For anti-Confederation editorialists and cartoonists, Confederation was a monster that was slowly but inevitably being assembled, piece by Canadian piece. I interrogate how the hydra can represent both serpentine dangers of Confederate secession and the insurmountable terror of Canadian Confederation with evidence culled from the Library and Archives of Canada—specifically, excerpts from the Ottawa Union, a newspaper published from 1861 to 1865 in the city chosen as the capital of Canada, and La Scie, a satirical journal published in Québec from 1863 to 1865—and songs and cartoons from the Civil War period available from the United States Library of Congress. In closing, I consider the relevance of the hydra as a symbol in more recent political cartoons.

Cartooning in the United States and Canada

Political debates and military conflicts are a consistent presence in the histories of the settler-invader colonies of Canada and the United States.[1] Since the work of Benjamin Franklin and George Townshend in the mid-eighteenth century, cartoonists have offered commentary on the political and military struggles of each country. Widely acclaimed as the first cartoonist in Canada, Townshend drew rude caricatures of his commander, British General James Wolfe, before fighting the French at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham (1759) in present-day Québec.[2] Townshend’s cartoons from the Battle of the Plains of Abraham—an event still referred to as “The Conquest” in modern-day Québec—showcase the tensions between various levels of authority. While the battle for British domination over French territory in the so-called New World was fought with military weapons, conflict amongst the British leadership played out through the power of the pen. Likewise, Québec cartoonists and Ontario editorialists lashed out with their pens against political leaders and the monstrous suggestion of Confederation in the 1860s.

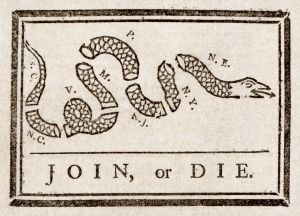

Franklin’s famous “Join, or Die” (1754) snake illustrated early geo-political ruptures in the American colonies, while his pro-militia “Non Votis”—widely cited as the first American political cartoon[3]—used figures from classical myth to illustrate one of Aesop’s fables. The latter image features Hercules in the clouds, indicating to a Pennsylvania wagoner that “God helps those who help themselves” (1746):

Benjamin Franklin, “Non Votis,” Plain Truth, 1746.

In The Political Cartoon, Charles Press comments on Franklin’s choice of proverb, noting that “eighteenth- and nineteenth-century cartoonists favored the classics, and historical and literary metaphors, since these were the common heritage of their cultured viewers” but “the imagery used may no longer be familiar, if it ever was.”[4] However, in his article on the use of Medusa, hydras, and other classical monsters in French caricature, William Kidd argues:

The historical prevalence and polyvalence of such imagery, and its availability for ideological deployment… suggest that it resonated with more general public attitudes, beliefs and mentalities (myths) and was underpinned by associations which made it a focal point for the unstated or the repressed.[5]

The intermittent references to Hercules and the hydra in Canadian and American political cartooning denote a certain fascination with this particular mythological symbolism. In keeping with Kidd’s assessment of the importance of recurring symbols in caricature, I trace the use of the hydra, with specific attention to the period from 1861 to 1867 in Canada and the United States. The trope of the hydra, in particular, shows how political conflicts during the early 1860s were imagined and imaged as terrifying, monstrous, and potentially undying anomalies. Like the multiplying heads of the mythological hydra, the United States and Canada have grown into multi-faceted societies of vast territorial and bureaucratic reach, making the hydra a useful symbol of political issues in the 1860s and since.

In classical myth, Hercules draws the many-headed hydra from its den by attacking it with fiery arrows. Each time Hercules destroys one of the heads with his club, two heads appear in its place. His troubles multiply before he calls for help and emerges victorious, as Sir James George Frazer’s translation of the tale relates:

But the hydra wound itself about one of his feet and clung to him. [… ] A huge crab also came to the help of the hydra. […] [Hercules] called for help on Iolaus who, by setting fire to a piece of the neighboring wood and burning the roots of the heads with the brands, prevented them from sprouting.[6]

Ultimately, Hercules and his helper, Iolaus, destroy the hydra with force and fire. This myth is referenced and reworked by cartoonists during the American Civil War and the debates around Canadian Confederation. Its use as a metaphor depends upon a shared frame of reference with audiences of the time, but a reconsideration of the changes wrought by cartoonists in their context-specific retellings of the tale offers illuminating insight into the chaotic, disruptive political atmosphere of the 1860s in North America.

Canadian Confederation and the American Civil War

From the earliest cartoons in the American and Canadian context, conflict and tensions—whether amongst Franklin’s Pennsylvania settlers or between officers in the British military—have provided rich fodder for satirists. By the mid-nineteenth century, with advances in printing technology, regularly published newspapers, along with illustrated journals like Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (USA, 1852-1922), Harper’s Weekly (USA, 1857-1916), La Scie Illustrée (Québec, 1865-1866), and L’électeur (Québec, 1866-1867), were on hand to document new conflicts in Canada and the United States. Such publications provided a forum for cartoonists and editorialists to critique political developments in both regions.

The American Civil War has been commemorated in northern states as a triumph of human rights on the issue of slavery, but at the time it was also understood as a struggle between Union and Confederate states to decide the course of the relatively young country’s future. Lasting repercussions from the Civil War have shaped the United States politically, culturally, and economically. The more immediate concern for British North America (now Canada) in the 1860s was that the well-armed American forces would turn north to annex the British territory after the Civil War’s end.[7] This anxiety was reinforced by the 1866 raid of New Brunswick planned by Irish veterans of the Civil War.[8] As Confederation talks were underway in Canada, American representatives were cultivating alliances abroad, and Union forces feared British (and Canadian) and French intervention on behalf of Confederate states. These overlapping political and military conflicts, coupled with general uncertainty about the future for either nation, led in part led to the official establishment of the Dominion of Canada with the British North America Act in 1867, which united the present-day provinces of Ontario, Québec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.[9]

The serpentine dangers of Confederate secession

The severed snake in Franklin’s “Join, or Die” was ultimately reassembled in James Gillray’s sympathetic “The American rattle snake” (1782) and through the establishment of the United States of America. Rather than an emblem of unification, however, during the American Civil War the image of the snake was deployed to represent the threat of treachery, destruction, and death to the unity of the nation. For example, an anonymous anti-Confederacy cartoon depicts a woman labeled “Dixie!” ensnared by the snake of secession (1860?). William Sartain’s “Young American crushing rebellion and sedition” (c1864) shows the Union as an infant Hercules defeating two snakes representing Southern rebellion and sedition. Although their use is less central to the illustrations, Frank T. Beard’s “Why dont [sic] you take it?” (1861), Louis Haugg’s “The Southern Confederacy a fact!!!” (1861), and Christopher Kimmel’s “The outbreak of the rebellion in the United States” (c1865) incorporate imagery of poisonous or stealthy snakes to convey the treachery of secession.

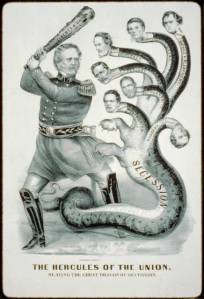

In M.H. Traubel’s “Triumph” (c1861), the “Hydra of human discord” spawns treachery and rebellion in the form of the southern Confederacy, led by the “reeking monster,” an alligator-headed King Cotton. Such serpentine imagery is also found in song lyrics regarding secession, such as “Our Country,” published by H. De Marsan: “Let not secession’s Hydra head, / With all its ill, on thee be shed.”[11] Another song by Frank I. Jervis included a similar sentiment: “See hydra-headed Faction fail / To tear the colors thou hast won, / While honest patriots will gladly hail / The natal day of Washington.”[12] Drawing from the classical tale of the hydra, as well as wide-spread rhetoric comparing the Confederacy to a snake, the prolific Currier & Ives published “The Hercules of the Union, slaying the great dragon of secession” (1861):

Currier & Ives. “The Hercules of the Union, slaying the great dragon of secession.” New York: 1861.

In this image, Union commander General Winfield Scott takes the role of Hercules, complete with the club of “Liberty & Union,” while Southern secession is represented by the seven-headed hydra. Each hydra head is labeled with a vice and the name of a Southern leader, as the Library of Congress record details: Hatred and Blasphemy (Robert Toombs), Lying (Alexander Stephens), Piracy (Jefferson Davis), Perjury (P. G. T. Beauregard), Treason (David E. Twiggs), Extortion (Francis W. Pickens), and Robbery (John B. Floyd). While they are all arguably traitors to the Union, two in particular stand out: General David E. Twiggs turned over United States Army posts in Texas to the South and former Secretary of War John B. Floyd allegedly provided supplies to the South.[13] Although their duplicitous treachery seems neatly represented by the duplicating hydra heads, it is worth remembering that Hercules instigated the attack on the hydra in the original story. Furthermore, the hydra had help from a giant crab (not pictured), and Hercules was unable to quell the beast with his assistant (also not pictured).

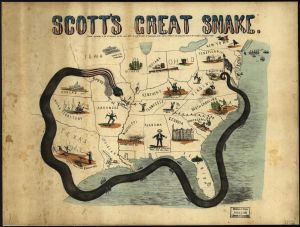

Scott developed the aptly named “Anaconda Plan” to blockade the Confederacy, so-called because of its likeness to an anaconda ensnaring the South:

However, Scott’s plan to slowly encompass the southern states and cut off Confederate supply lines was considered inconsistent with an optimistic belief in the North that the conflict would be a brief one. This early reluctance to end the Southern “Rebellion” through a coordinated blockade contributed to protracted military engagement, leading to hundreds of thousands of deaths.[14] Ultimately, the battle lasted well beyond Scott’s 1861 retirement from active duty.

Although the figure of Scott appears to have the upper hand in the Currier & Ives print, as he is astride the hydra’s tail and armed with both a club and a sheathed sword, he could very easily become entangled in the serpent’s twisting tail or enmeshed in a battle against a never-ending proliferation of hydra heads in support of the South. Indeed, the 1861 image offers an uncannily accurate prophecy of the bloody, seemingly never-ending conflict to follow. The visionary hero is forced to retire his club, and the purifying fire brought by Hercules’s helper is nowhere in sight. Perhaps this absence helps account for the hydra’s tenacity and longevity, demonstrated today by such totems as Confederate flag bumper stickers.

The insurmountable terror of Canadian Confederation

While the United States was being torn asunder, Canada was being pieced together like Frankenstein’s monster. An 1865 editorial in the Ottawa Union expressed disgust with the monstrous expanse of the new nation:

We are… asked to be silent while a nation is being born; but seeing its hyrdahead we fear the malformation of the creature. Head on the Pacific; heels on the Atlantic, with its left arm grasping the north pole and its right looking to Washington, we fail to be convinced of the strength of its ligaments that are expected to hold its ghestship’s carcass together. … What is Upper Canada worth today? … [O]ne half of its entire value would fall to meet the demand of this thing they call a new nation. Twenty millions of dollars would not establish communication with its feet: twenty millions more would fail to reach its frigid head…[15]

This editorial echoes sentiments expressed about secession in American song lyrics. While the lyrics critique the terrible dissolution of the American Union, in this case, the unification of the Canadian provinces is seen as monstrous. For this editorialist in the perhaps misnamed Ottawa Union, the vast territorial expanse of Canada—from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean with northern and southern aspirations—will prove ungainly, unsightly, and uncoordinated, with the head (or the federal capital, Ottawa) unable to communicate with its feet (the far-off provinces, at a time when transportation and communication were more expensive and time-consuming efforts). The word “thing” highlights the ineffable nature of Canadian Confederation, while the terms“creature” and “carcass” provide equally unflattering commentary on the future of Canada. Calling the nascent nation a “hydrahead” bespeaks the unwieldiness of the expansive Canadian territory as well as the difficulty of reigning in multiple competing political demands within the huge space. Although this warning was issued when Canada claimed a smaller portion of North America than it does today, this editorial predicts ongoing issues of communication with areas deemed marginal or remote, as well as intense regionalism and political variegation within the contemporary framework of Canada.

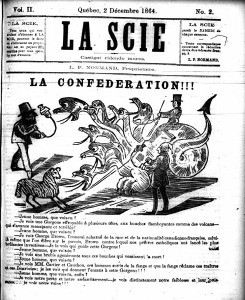

The rhetoric of the English-language press echoed the monstrous imagery of the French-language press. The cover of La Scie in December 1864 featured a seven-headed hydra under the title « La Confederation!!! » :

The caption reads: “‘Young man what do you see?’ ‘I see a hydra with several heads, with flaming mouths like volcanoes and it is coming towards us menacing and terrible. […] I see George Brown, the staunch enemy of French Canadian culture and nationalism […] guiding this Hydra. […] I see MM Cartier and Cauchon […] giving incense to this hydra!!!! […] I see our end and our annihilation – I distinctly see our weakness and their strength… I see our ruin.’” (Translation courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada.)

In this image, the sacrificial lamb represents Québec as an offering to the monstrous Confederation hydra, ridden by George Brown, who is considered one of the Fathers of Confederation. The cartoonists predicts the demise of French Canadian culture, and shows Québec politicians George Etienne Cartier—another Father of Confederation—and Joseph Cauchon—who first opposed, then supported Confederation—appeasing the monster with incense, blessing the hydra’s presence rather than defending the lamb through force or self-sacrifice. The last line states that Québec will be ruined by joining Confederation. The treachery here is complete, fatal, and fatalistic. For this cartoonist, Confederation means union with English Canada and the death of French-Canadian provincial autonomy and cultural, religious, and linguistic practices.

Hercules is missing from the La Scie tableau, making the allusion to the classical myth deliberately incomplete. While Scott, the impeccably uniformed Hercules (above), ultimately retires in real life, the Hercules of Québec never even exists. The lamb’s sacrifice to the hydra of Confederation is a fitting metaphor for what many Québécois(e) consider a period of oppression that began with The Conquest. The Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, an incredibly close vote (50.58% to 49.42%) not to separate from the rest of Canada in 1995, and the subsequent recognition of Québec as a “distinct society” within the federal framework are but a few examples that speak to the uneasy assemblage that Confederation left in its wake.

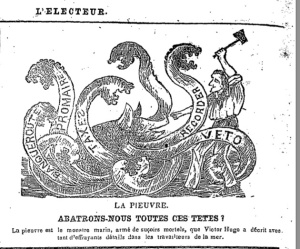

In combative contrast, a political cartoon in L’’électeur offers armed resistance in the form of a character wielding an axe against « La Pieuvre » (“The Octopus”), a monstrous hybrid with the body of a boar and eight octopus arms with labels like “bankruptcy” and “taxes” (1866):

Although the figure with the raised axe has a tool to begin the fight, his left leg is already partially ensnared by the sea monster, again leaving one with little hope for the political future of Québec amidst such troubles as “veto” powers.

In keeping with this dour tone, the Canadian Illustrated News shows seven-headed “The Election Monster” trampling Québec (the French-speaking province) and New Brunswick (the only officially bilingual, French and English, province in Canada), with its eyes on Ontario, Nova Scotia, Manitoba, and British Columbia:

Québec’s borders are threatened and trampled by the hydra, whose heads have labels like “perjury,” “intrigue,” “calumny,” and “violence.” As in « La Confederation!!! » , no Hercules appears to fend off the hydra. Unlike the American use of the allegory of Hercules fighting the hydra, the overwhelming appearance of the hydra in both La Scie and the Canadian Illustrated News—as the figure of the hydra in both illustrations take up the majority of the image—reinforces the sense that the Canadian alliance is monstrously ill-advised and ill-fated. Furthering this point, a faux birth announcement in the Nova Scotia Eastern Chronicle and Pictou County Advocate read: “Born: On Monday morning last, at 12 […] a.m., (premature) the Dominion of Canada — illegitimate. This prodigy is known as the infant monster Confederation” (3 July 1867, page 3, emphasis added).

The internal struggle for legitimacy continues in both settler-invader colonies. Any national consensus about how federalism should operate in a democratic system, a consensus sought since the Confederation debates in Canada and since before the battles of the American Civil War in the United States, remains unrealized. Instead, multiple (and multiplying) challenges to peaceful co-existence at the local, national, and international levels hamper efforts at inter-cultural understanding and accommodation, despite the American emphasis on heroic, Herculean images to accompany the troublesome hydras of the nation’s history.

The hydra lives on and multiplies

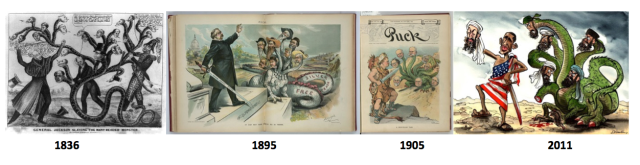

American presidents have enjoyed a long tenure in political cartoons as Hercules fighting various hydra heads with a sword, from Andrew Jackson (H.R. Robinson’s “General Jackson slaying the many headed monster,” 1836) and Grover Cleveland (Louis Dalrymple’s “It can not pass while he is there,” 1895) in the nineteenth century to Theodore Roosevelt (J.S. Pughe’s “A herculean task,” 1905) and Barack Obama (Andy Davey’s “Bin Laden Hydra,” 2011) in the twentieth. In contrast to this heavily armed patriotism, Robert Chambers depicted Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker in the clutches of a “Hydra-Headed Giant” (1957):

In this case, the giant is armed with the club of “Non-confidence vote” and Diefenbaker is left small and helpless in the hand of “Splinter parties,” offering a less-than-heroic iteration of the Canadian Prime Minister. Perhaps the Ottawa Union put it best in 1865: “Canada stands at this time in the rather anomalous position of a country requiring to be protected against itself.”[16] The struggle of the diminutive Prime Minister to coordinate the needs of a massive territory with a gigantic, armed, multi-party system harkens back to the concerns about an unmanageable “ghestship’s carass” that the Ottawa Union expressed in advance of Confederation.

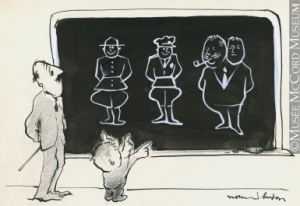

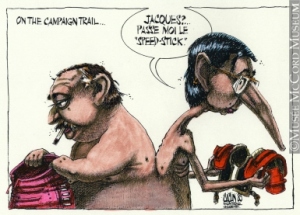

Québec political cartoonists Normand Hudon and Aislin share a similarly dim view of Canadian politicking. Both have depicted the type of two-headed “monstrosity” decried by the Ottawa Union:[17]

Normand Hudon, “Federal, provincial, two-headed…” The Montreal Gazette, c1960. Courtesy of the McCord Museum.

Aislin (Terry Mosher). “Parizeau and Bourassa in the Locker Room,” 1989. Courtesy of the McCord Museum.

While the seven-headed hydras of Secession and Confederation have been replaced by other threats—such as the U.S. Senate (Pughe, 1905), the Québec politicians Jacque Parizeau and Robert Bourassa (Aislin, 1989), and terrorism (Davey, 2011)—the appearance of monstrosities at moments of national uncertainty lives on as a trope in political cartooning. Although the monsters remain in most systems, cartoonists remain vigilant, updating tales from antiquity to add satire to the chaos of political life. Only time will tell where the next hydra will emerge and whether heroes will rise to the occasion or offer more lambs to appease the beast.

Acknowledgements

Research for the Canadian component of this comparative study was conducted as part of Carleton University Professor Anne Trépanier’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada grant project « Imaginations d’un Canada : représentations de la Confédération (1864-1867) » along with Sarah Spear, Elaine Radman, and Ryan Lux. I would like to credit Anne Trépanier and Emily Hazlett thoughtful critique and feedback for this article, Sarah Spear for unpacking the religious symbolism in « La Confederation!!! » at the Trent-Carleton Graduate Conference in March 2013, Elaine Radman for locating and sharing the image of « La Pieuvre » and the article from the Eastern Chronicle and Pictou County Advocate, and Ryan Lux for locating and sharing excerpts from the Ottawa Union. I would also like to thank Louise Le Pierres at the Chronicle Herald for locating and scanning the microfiche of the “Hydra-Headed Giant.”

Image List (most images link to sources)

Aislin (Terry Mosher). “Parizeau and Bourassa in the Locker Room,” 1989. Courtesy of the McCord Museum.

“[Anti-Confederacy cartoon showing “Dixie” being entwined by the snake of secession].” c1860. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

Currier & Ives. “The Hercules of the Union, slaying the great dragon of secession” New York: Currier & Ives, 1861. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

Dalrymple, Louis. “It can not pass while he is there,” 1895. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

Davey, Andy. “Bin Laden Hydra,” 2011.

Elliot, J.B. “Scott’s great snake.” 1861. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Franklin, Benjamin. “Non Votis,” Plain Truth, 1746. Courtesy of LibraryCompany.org.

Hudon, Normand. “Federal, provincial, two-headed…” The Gazette, c1960. Courtesy of the McCord Museum.

“Hydra-Headed Giant.” Halifax Chronicle Herald, 18 June 1957: 4. Courtesy of The Chronicle Herald archives.

« La Confederation!!! » La Scie 2.2. Montreal. 2 December 1864: 1. Courtesy of the University of Ottawa Libraries.

« La Pieuvre. » L’’électeur: politique, caricature et critique 1.11. Québec: A. Guérard. 28 July 1866: 2. Courtesy of Early Canadiana Online.

Nichols, E.W.T. “The great American What is it? chased by Copper-heads.” Boston, 1863. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

Pughe, J.S. “A herculean task.” 1905. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

Robinson, H.R. “General Jackson slaying the many headed monster.” 1936. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

Sartain, William. “Young American crushing rebellion and sedition.” Philadelphia: William Sartain, c1864. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

“The Election Monster.” Canadian Illustrated News 4.5. 31 January 1874: 65. Courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada.

Traubel, Morris H. “Triumph.” Philadelphia: M.H. Traubel, c1861. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress.

Footnotes and Citations

[1] “Settler-invader colony” is a term used in post-colonial studies to indicate recognition of ongoing, unresolved Indigenous land claims alongside permanent settlement by immigrant communities.

[2] Mosher, Terry (ed.). Caricature / Cartoon Canada. Québec: Linda Leith Publishing, 2012: 6-8.

[3] See, for example: Joseph A. Leo Lemay’s The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 3, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009: 5; Donald Dewey’s The Art of Ill Will: The Story of American Political Cartoons, New York University Press, 2007: 3.

[4] Press, Charles. The Political Cartoon. London & Toronto: Associated University Presses, 1981: 29.

[5] Kidd, William. “Marianne: from Medusa to Messalina: psycho-sexual imagery and political propaganda in France 1789-1945.” Journal of European Studies 34.4. December 2004: 339.

[6] Apollodorus. “Apollod. 2.5.2.” The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Available from Perseus Digital Library, ed. George W. Mooney.

[7] Morton, Desmond. A Short History of Canada. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2001: 89.

[8] This raid is partially justified by the following, perhaps apocryphical, lyrics:

“We are the Fenian Brotherhood, skilled in the arts of war,

And we’re going to fight for Ireland, the land we adore,

Many battles we have won, along with the boys in blue,

So we’ll go and capture Canada, for we’ve nothing else to do.”

[9] See “British North America Act, 1867.” Department of Justice, Canada.

[11] “Our country.” New York: H. De Marsan. n.d. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress and Duke University Libraries Digital Collection. Emphasis added.

[12] Jervis, Frank I. “Washington, a birthday song.” Loag, Pr. cor. 4th. & Chestnut. 1864. Courtesy of the United States Library of Congress. Emphasis added.

[13] See complete entry for “The Hercules of the Union, slaying the great dragon of secession.” Coutesy of the United States Library of Congress.

[14] Precise estimates of the death toll during the Civil War vary.

[15] “The Liberal Party.” Ottawa Union. 7 September 1865. Courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada. Emphasis added.

[16] “Confederation.” Ottawa Union. 9 December 1865. Courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada.

[17] “The Siamese Twins.” Ottawa Union. 11 October 1865. Courtesy of the Library and Archives Canada.

UPDATE:

Pingback: Les visages de l’Hydre de Lerne dans la culture populaire contemporaine, du cinéma aux jeux vidéo – Antiquipop | L'Antiquité dans la culture populaire contemporaine